Even as BP’s blown well a mile beneath the surface in the Gulf of Mexico continues to gush forth an estimated 70,000 barrels of oil a day into the sea, and the fragile wetlands along the Gulf begin to get coated with crude, which is also headed into the Gulf Stream for a trip past the Everglades and on up the East Coast, the company is demanding that Canada lift its tight rules for drilling in the icy Beaufort Sea portion of the Arctic Ocean.

In an incredible display of corporate arrogance, BP is claiming that a current safety requirement that undersea wells drilled during the newly ice-free summer must also include a side relief well, so as to have a preventive measure in place that could shut down a blown well, is “too expensive” and should be eliminated.

Yet clearly, if the US had had such a provision in place, the Deepwater Horizon blowout could have been shut down right almost immediately after it blew out, just by turning of a valve or two, and then sealing off the blown wellhead.

A relief well is ”too expensive”?

The current Gulf blowout has already cost BP over half a billion dollars, according to the company’s own information. That doesn’t count the cost of mobilizing the Coast Guard, the Navy, and untold state and county resources, and it sure doesn’t count the cost of the damage to the Gulf Coast economy, or the cost of restoration of damaged wetlands. We’re talking at least $10s of billions, and maybe eventually $100s of billions. Weigh that against the cost of drilling a relief well, which BP claims will run about $100 million. The cost of such a well in the Arctic, where the sea is much shallower, would likely be a good deal less.

An oil spill under the ice would be impossible to stop or clean up.

An oil spill under the ice would be impossible to stop or clean up.

Such is the calculus of corruption. BP has paid $1.8 billion for drilling rights in Canada’s sector of the Beaufort Sea, about 150 miles north of the Northwest Territories coastline, an area which global warming has freed of ice in summer months. and it wants to drill there as cheaply as possible. The problem is that a blowout like the one that struck the Deepwater Horizon, if it occurred near the middle or end of summer, would mean it would be impossible for the oil company to drill a relief well until the following summer, because the return of ice floes would make drilling impossible all winter. That would mean an undersea wild well would be left to spew its contents out under the ice for perhaps eight or nine months, where its ecological havoc would be incalculable.

BP and other oil companies like Exxon/Mobil and Shell, which also have leases in Arctic Waters off Canada and the US, are actually trying to claim that the environmental risks of a spill in Arctic waters are less than in places like the Gulf of Mexico or the Eastern Seaboard, because the ice would “contain” any leaking oil, allowing it to be cleared away. The argument is laughable.

This is not like pouring a can of 10W-40 oil into an ice-fishing hole on a solidly frozen pond, where you could scoop it out again without its going anywhere. Unlike the surface of a frozen pond, Arctic sea ice is in constant motion, cracking and drifting in response to winds, tides and currents. Moreover, the blowout in the Gulf has taught us that much of the oil leaked into the sea doesn’t even rise to the surface at all. It is cracked and emulsified by contact with the cold waters and stays submerged in the lower currents, wreaking its damage far from wellhead and recovery efforts.

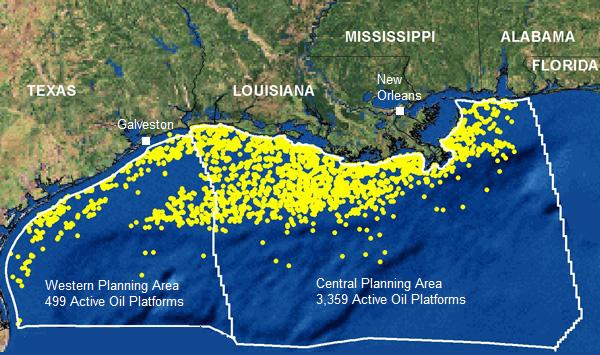

Active oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico

Active oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico

Finally, as difficult a time as BP has had rounding up the necessary containment equipment and personnel in the current blowout 50 miles from the oil industry mecca of Texas and Louisiana, the same task would be far harder to accomplish in the remote reaches of the Beaufort, far above the Arctic Circle, where there aren’t any roads, much less rail lines or airports.

In fact, it was the remoteness of the Arctic staging area, and the lack of infrastructure, that has been the oil industry’s main argument against a mandatory simultaneous relief well drilling requirement for offshore Arctic drilling. The industry claims it would be “too difficult” to drill two wells simultaneously, as this would require bring in and supplying double the personnel, and two separate drilling rigs.

In a hearing in Canada’s Parliament last week, Ann Drinkwater, president of BP Canada, told stunned and incredulous members of Parliament that she had never compared US and Canadian drilling regulations. In fact, whether by design or appalling ignorance, she had precious little in the way of information to offer them about anything to do with drilling rules, effects of spills, or containment strategems. All she wanted was relief from “expensive” regulation, so BP could go about its business of putting yet another region of the earth and its seas at risk in the pursuit of profits.

Asked if BP knew how it would clean up oil spilling out under the winter ice in a blowout, Drinkwater told the parliamentary hearing, “I’m not an expert in oil-spill techniques in an Arctic environment, so I would have to defer to other experts on that.”

“You’d think coming to a hearing like this that British Petroleum would have as many answers as possible to assure the Canadian public. We got nothing today from them,” groused Nathan Cullen of the left-leaning New Democrats, after hearing from the ironically named Drinkwater.

The fundamental problem in the US is that politicians purchased by campaign contributions are unwilling to look at the real risks of offshore drilling, whether on the two coasts or up in the Arctic region. With luck, maybe at least the Canadian government will conclude that such drilling in their northern seas makes no economic or environmental sense. In both countries, the amount of oil provided from offshore drilling would, over the next decade, be less than could be saved by simply making automobile mileage standards stricter.

All this is even more true when the drilling in question is in the fragile ecological environs of the Arctic Ocean.