GANGSTERS OF CAPITALISM: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire; St. Martin’s Press, 2021, 412 pages.

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

-Attributed to Mark Twain

The tale journalist/historian Jonathon M. Katz tells in his new book, Gangsters of Capitalism, is an epic story that “rhymes” a lot with our current nightmare. It’s a story that helps us understand an important feature of American history, one that’s often muted and marginalized. It’s perfect for what Barack Obama has dubbed the nation’s Third Reconstruction, and it should be part of high school history classes. Plus, if done right, there’s a film in this material that could be as dramatically compelling as Lawrence of Arabia.

Lowell Thomas, a popular journalist in the early 20th century, published a popular book on T. E. Lawrence titled With Lawrence of Arabia; Thomas is actually a character in the film. He also published a book called Old Gimlet Eye on Marine General Smedley Butler; the title refers to his nickname from an eye wound. The book is ghost-written in the first person in a folksy, macho style. Katz cites the book periodically, but he seems to avoid some of its stories. I’ve often wondered how much of the Old Gimlet Eye was accurate and how much was tall tales like those in the dime novels about Wild Bill Hickok and Billy the Kid. Butler’s story as a military gunman for big business is set in the same terrain of fact, myth and legend.

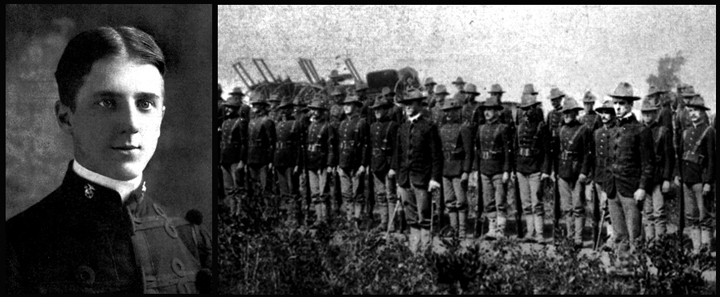

[ Son of a Quaker US congressman, Smedley Butler was both a charming conversationalist and a tough, vulgar Marine. ]

The life of Philadelphia Quaker and Marine Major General Smedley Darlington Butler is well known and revered among people in the anti-war movement. Ironically, he’s also a hero amongst Marines and in other gung-ho militarist camps. The Veterans For Peace chapter in Boston has called itself The Smedley Butler Chapter ever since the beginning of that national organization in 1985. Speaking on MSNBC, Malcolm Nance, a Black, former US intelligence officer, now an expert on right-wing domestic terror, tells of having “Smedley Butler memorabilia at home in my man cave.”

I once spoke briefly with Afghanistan commander General Stanley McChrystal, who was fired by President Obama for bad-mouthing him in a Rolling Stone interview. When I mentioned Butler’s name, the retired four-star general beamed. He’d correctly pegged me as an anti-war lefty, so the conversation had been cautious, but Butler’s legend was something we could both agree on — for different reasons — since Butler holds a prominent spot in the minds of modern practitioners of counter-insurgency doctrine like McChrystal. It’s the aspects of modern warfare that incorporate elements of humanitarianism and public relations — alongside much better funded campaigns of killing and destruction.

I’ve been a student of the Smedley Butler story for over 20 years, writing about him in essays, scribbling an unfinished screenplay, speaking of his life in classrooms and on the radio. As a writer too familiar with the mainstream’s margins, it’s clear to me Smedley Butler’s rather complicated, even self-contradictory, story has essentially been embargoed from mainstream culture. Why? It’s way too complicated and nuanced for the public arena of modern militarism. Our mainstream militarized culture always follows the first rule of warfare, that the first casualty is truth. The warrior types respect Butler’s incredible military prowess, especially his capacity as a fearless and ruthless killer and his effective leadership of other ruthless killers. He accumulated this legend, by the way, as a quite diminutive, even scrawny, man; there’s a bit of a fighting cock in his image. For his militarist fans, his late-in-life anti-war sentiments, what enamors Butler to anti-war types, are a disappointment, something to be ignored, diminished or dismissed as a little bit screwy, maybe even demented.

Katz convincingly suggests Butler’s war-weary stirrings began in Haiti, where he oversaw the incredibly bloody killing of greatly outgunned, uneducated Haitian fighters opposed to the invasion by his US Marines. Katz has read reams of Butler’s letters back to his family, and he proposes that Butler is suffering from a “moral injury,” a modern term that has evolved out of the post-Vietnam discussion over Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). A moral wound is a metaphor for the idea that one can become trapped inside a monstrous enterprise and not really understand the true horror of it until it’s too late. One can understand it psychologically, as it might be described in the DSM, or one can see it simply as a dramatic reality of living — in this case, the hinge point for a man’s revised view of his own life.

Here Come The Marines!

Butler’s Marine career began in 1898, when a very athletic young Smedley attended the Quaker Haverford School on the Philadelphia Mainline. The nation was over the Civil War and was bursting at the seams with railroads and other industries. It was an age of robber-barons. Also bursting at the seams, the 16-year-old Smedley lobbied his mother, a Hicksite Quaker, to influence his father, a US congressman, to allow the boy to join the newly expanding Marine Corps. Young Smedley had read in the paper that the Marines — Navy shipboard infantry — were to play a much expanded role engaging with the poor, benighted peoples of the world. Expanding the Marine Corps. enabled the rise of US imperialism as we have come to know it.

[ 16-year-old Smedley Butler in his new 2nd lieutenant’s uniform off to Guantanamo. Later, in the Philippines, standing , at right, before his men. ]

Butler arrives at Guantanamo Bay by ship in the fancy, tailored uniform of a second lieutenant that his mom helped him arrange. He immediately runs into some very disheveled and seasoned Civil War vets who find him amusing. They quickly straighten the kid out and set him on what will become a glorious 42-year military career that began in Guantanamo and went on to the Philippines, the 1900 Boxer Rebellion in Northern China, the Philippines again, Central America, the Canal Zone, Haiti and China again in 1926, at which point he’d become a major general.

“While the Marines were learning to land on foreign beaches,” Katz writes, “the bankers were learning to expand beyond the US borders. … They experimented with financing foreign wars. … It was only a matter of time before the investors wanted to select the leaders of the countries they were investing in as well.”

Katz was the Associated Press bureau chief in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, during the massive 2010 earthquake. He covered relief efforts for a year afterward and wrote an award-winning book, The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster. The title alone is a tale of corruption and horror. Katz won the Medill Medal for Courage in Journalism.

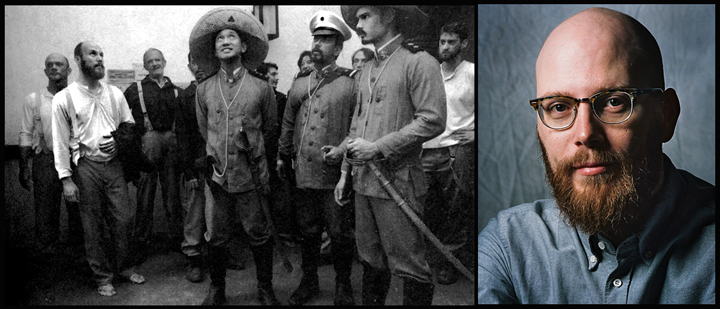

[ Author Jonathon Katz, left foreground, playing an American POW in a 2018 epic Philippine film called Goyo: Boy General (available on Netflicks) about an arrogant, young ladies’ man general in 1899. Suffering traumatic battle memories under the relentless lethal assault of the US Army, the boy becomes a man. (At the time, Butler and his Marines were working the other end of the island.) The film’s narrator, a polio-ridden lawyer known as “the brain of the revolution”, concludes that the American imperialists’ view that Filipinos were “like children” was, in 1899, tragically true. Below is the real “boy general” in a photo session dramatized in the movie. Like the Cacos in the Haitian Battle of Fort Riviere (see directly below) Goyo is killed defending a mountaintop redoubt his outgunned forces had been driven to. ]

Besides real world experience relevant to the Butler story, Katz spent over five years reading everything under the sun on the man. The book alternates between the Butler story and sections about Katz’s personal travels with guides to places like the Haitian mountaintop redoubt Fort Riviere where the Cacos guerrilla fighters were making their last stand following the Marine invasion of 1915. Butler famously assaulted the fort with a company of Marines.

To help the reader understand how incredibly difficult it was for Butler and his Marines to assault that mountain, especially toward the very top where the stone fort had been built, Katz actually goes there (it’s 20 miles from Cap Haitien in the north), hires a guide and with some difficulty finds the right mountain and climbs to the top, where the wreckage of the fort sits after being dynamited in 1915 by the Marines following their victory. His Haitian guide punks out halfway up the rigorous climb, and Katz goes on alone, driven by his own determination.

“As I struggled up a precipice between the peak and the valley, it became clear why these particular Cacos had chosen this mountain as the place to make their last stand. I also realized how deeply committed Smedley Butler, and every Marine who climbed to the summit with him, had to have been to wiping out every last vestige of Haitian resistance.”

[ An artist’s rendering of US Marines in 1915, their Springfield rifles fitted with bayonets, bursting out of a tunnel into a courtyard of the Cacos’ Fort Riviere. Butler is at center shooting with his automatic Colt .45. ]

Butler’s Marines came upon a narrow tunnel they speculated led into the fort, above. Just thinking about entering such a tunnel gave me the willies — akin to the terrifying idea of dropping into a VC tunnel. Smedley and his men crawled single file into the three by four foot tunnel and came out, to their surprise, into a courtyard full of furious guerrillas. The shooting started immediately. Due to surprise and vastly superior weaponry (the Cacos had machetes and few rifles) the trained Marines began gunning down the Cacos fighters, forcing some to leap from a cliff. Those who survived the fall were cut down by a machine gun.

Deputy Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt visited Haiti and heard the story; when he got back to Washington, he put Butler in for his second Medal of Honor. The first had been for actions in Mexico during the invasion of Veracruz.. He refused that medal, which was for a brief spying mission where he posed as a civilian businessman. He felt he hadn’t earned the honor. He was ordered to accept it, which he did.

As the ranking officer in Haiti, Butler hit a moral wall. He writes home of having nightmares and not being able to sleep. He lobbies hard for his wife, Bunny, and his three kids, to join him in Port-au-Prince. The US has joined the war against Germany, and Butler wants to be part of that more honorable fight. The mass killing of poor, uneducated peasants and the racism he and others exhibited in places like Haiti began to eat at him. The problem was he was so damn good at imperial soldiering that US leaders had come to rely on him in Haiti. They didn’t need him in France. It had taken an awful lot of killing to pacify the Cacos rebels, and he was now charged with keeping the occupied black island nation under control. He knew many Haitians referred to him as “the devil.”

The Haitian legislature was opposing a new constitution, which was strongly pursued by the Americans; the stumbling block was a clause allowing foreigners to own land, which was code permitting wealthy capitalists to buy up Haiti’s extraordinarily rich agricultural land and virtually enslave Haitians to work that land. When the legislature balked, Butler took a contingent of heavily armed Marines into the legislature and dramatically ordered his men to cock their rifles, which were pointed at the leaders. They signed the new constitution. The action dissolved the legislature, which was not re-established for 12 years. At the point of his Marine guns, Butler had killed Haitian democracy.

A Haitian Encounter

I was in Haiti in 1986 just after Baby Doc was pushed out. Haitians were ecstatic. I was visiting a doctor friend working with Haitian health care workers in Plaisance, a mountain town in the middle of the country along the major highway from Port-au-Prince in the south to Cap Haitien in the north. Butler and his Marine-supervised Haitian police force (known as the Gendarmes) oversaw the building of this road connecting the two commercial ports; it was a highway designed by Marines purely for military and commercial purposes. I had a rental car and was aware of peasants with children and animals walking along the highway in both directions. My memory has distilled down to the image of a huge black Mercedes Benz with tinted windows passing me at 90MPH and peasant families leaping to the shoulders as it flew by.

One day I was driving my little banged-up rental from Plaisaince south to Port-au-Prince, and at the market town of L’Ester I ran into an amazing confrontation. Traffic on the highway had stopped both ways; it was Noon and the market had literally overrun the highway. Eager drivers traveling north and south attempted to pass using the shoulder or the opposite lane, thus, it was two lanes of traffic facing each other at a standoff. I sat amazed and watched khaki-dressed cops in front of my windshield beating passing market people with truncheons to get them to move off the roadway so they could begin to get the automobiles going north and south straightened out. After reading Katz’s history of the US Marines and this highway, I suddenly realized, 35-years later, what I had witnessed was a high-noon collision of top-down, strategic, imperial highway design — construction overseen by Smedley Butler — and the eternal, unruly free spirit of Haitian people doing what they were led to do at a huge market at Noon. Chaos was inevitable.

A disabled young Haitian painter living in Plaisance had asked me for a ride to Port-au-Prince. I looked over at him next to me and shook my head. I must have looked a bit worried. He grinned.

Here’s how Katz describes getting around in the city of Port-au-Prince:

“Each day, its arteries clog with the cars and foot traffic of people trying to eke out a living, embittered by a broken system designed with imperial control, not their lives, in mind.”

Katz makes the case well that the dedicated and ruthless actions of men like Smedley Butler were instrumental in keeping Haiti at the very bottom of the pile in the western hemisphere. In the 18th century, Haitians had fought hard to obtain their liberty and dignity from France, forcing Napoleon to give up Haiti as an exploited colony. This must have terrified slaveholders in the newly created United States. Ever since then, the US has done everything it could to assure the island remained a perennial disaster zone reduced in mainland minds to a resort island with a frisson of mummy horror movies. Everything is couched in terms of beneficently lifting the island out of its darkness.

As in Central America, the land-grabbing process made peasant subsistence living difficult to impossible, leaving the peasantry with no other option than virtual slavery. Under Butler’s military rule, Haitians were given a choice: Work on the strategic highway or pay a special tax. Since they had no money, they had to work on the highway. Katz quotes Haitian historian Roger Gaillard on why it’s accurate to label what Butler enforced as “slavery.” Gaillard reels off a list of six things that Haitians were subject to under Butler’s rule. His list ends sarcastically with this:

“Sixth, when you tried to run away, they killed you. Now, then, is that not slavery?”

Besides Haiti, Butler served in Panama after Teddy Roosevelt stole the isthmus from Colombia to build the US Canal Zone. He strong-armed his way around Nicaragua for the Brown Brothers Bank in New York. The same with Honduras, a word in Spanish than means “depth” or even “ditch.” Katz writes of Butler’s Marines waiting on board ship off the Atlantic coast of Honduras as political unrest develops inland. “The rebels here are becoming rather restless,” Butler writes his beloved mother, Maud. “Our company is to go ashore if anything happens so I am anxiously waiting for a nigger to throw a stone.”

Today, Honduras is like Haiti, a disaster. A 2009 coup removed democratically elected President Manuel Zelaya, which opened the dirt-poor nation to more drug trafficking and more US military bases. The murder rate rocket upward. President Obama and Secretary of State Clinton quickly recognized the coup government. Just this week we learned the former president of Honduras (part of the post-coup regime) has been arrested and is expected to be extradited to the US for trial on drug crimes; the ex-president’s brother is already serving a life term in the United States. And in a hopeful turn of events, the wife of removed President Zelaya, Xiomara Castro, was recently elected president.

As an attending Quaker in the 1980s, I was surprised to read how much Maud Butler encourages her son’s bloody military career. Did she at all understand what was really going on? Or was it all about family prestige and power? Katz says this about the letter, above: “Maud may have objected to the coarseness of the racial epithet, though likely not the militaristic sentiment.” His tough Quaker mother and his congressman father — a man intimately involved in legislating money for the imperial Navy and Marine Corps — were without doubt powerful forces propelling Butler’s career forward. He always referred to them in letters as “the” and “thou.” This opens the question Katz doesn’t address: How much did Butler’s Quaker upbringing account for his eventual turning against his own military career?

The Major General With the Bad Attitude

Butler eventually did get to France. But instead of the combat unit he wanted, he was assigned to run a replacement center. Disappointed as he was, he characteristically did his job with incredible dedication and energy; he was a “soldier’s general” to the max, always looking out for his men’s well being and interests, building esprit-de-corps from the bottom-up. Unlike many military officers, he had a visceral disdain for what is known in the military ranks as “chicken shit,” which often had something to do with lazy or cowardly leadership. He might be vulgar, but he was a straight shooter.

Katz devotes a chapter to Butler’s two-year hiatus from the Marines when, beginning in 1923, he becomes police commissioner of Philadelphia. Immigrants and blacks from the south are swarming into Philly, and gangsters are plaguing the city. Crime is a big issue. Butler’s creation and training of a militarized police force in Haiti is what attracts city leaders in what was known as “the Republican Organization.” After two years, Butler is forced out for running raids on the wrong establishments. As Philly Congressman Ozzie Myers put it so well a half-century later on his ABSCAM tape: “In this town, money talks and bullshit walks.” Militarized cops are great as long as they terrorize poor, black people and don’t disturb the powerful.

Back on active duty, in 1931, Secretary of the Navy Charles Adams (great grandson of John Quincy) court-martials Major General Butler for calling Benito Mussolini a “bum” in a speech in Philadelphia. Unfortunately, Butler and Adams are not friends; Butler had once introduced Adams during “a testy inspection” of his unit at Quantico this way: “Gentlemen, I want you to meet the Secretary of the goddamn Navy.” As a general who had not attended Annapolis, the Mussolini flap helped kill his being named Commandant of the Marine Corps, traditionally given to the ranking general, which he was.

At issue was a story told to Butler by reporter Cornelius Vanderbilt IV (great, great grandson of the famous “Commodore”) about riding with Mussolini, who was driving a Fiat, when he ran over a small child who dashed in front of the car. The young writer was horrified. While he denied it at first, in a 1959 memoir, Vanderbilt wrote: “I felt a hand on my right knee and I heard a voice saying, ‘Never look back, Mister Vanderbilt, never look back in life.’ ”

Despite Mussolini’s popularity in the US at the time, Butler beat the rap by going public around the country on a speaking tour until Adams was forced to withdraw the charges. Butler discovers he has a gift for public speaking, which he will employ for the rest of his life, once in a failed Republican run for US Senate.

[ Butler speaking to the Bonus March veterans in Washington DC: “Who in the hell has done all the bleeding for this country . . . but you fellas?” he asked his beloved soldiers. Nine days later the camp was attacked and burned out by US military forces led by General Douglas MacArthur. ]

In 1932, Butler was asked to speak before the Bonus Army’s encampment in Washington DC. It was the Depression, and these angry WWI veterans wanted the bonus money promised to them for their service, but the government was not going to pay it until 1945. They roared when Butler told them in his bantam rooster style: “This is the greatest demonstration of Americanism we have ever seen. . . . Who in the hell has done all the bleeding for this country, and for this law, and this Constitution anyhow, but you fellas? . . . But don’t — don’t! –take a step backward. Remember that as soon as you haul down your camp flag here and clear out — every one of you clears out — this evaporates in thin air.”

While officialdom was encouraging the protesters to leave, Butler’s speech inspired many to remain. Nine days later, under the leadership of General Douglas MacArthur and against orders from President Hoover, the encampment was violently shut down with gas and burned out. There were several deaths and scores of injuries. MacArthur later said he was defending against a communist revolution.

[ Butler being sworn in as Philadelphia police commissioner by the mayor who pushed him out two years later for raiding the wrong places. And Butler speaking of his HUAC testimony in the so-called Business Plot. Note the nifty, very PR-savvy graphic of the Marine insignia behind Butler. ]

The rhymes with January 6th really pile up when Katz gets to his final chapter focused on the so-called 1933 Business Plot, which involved Wall Street plutocrats scheming to replace the traitor to his class FDR with a fascist “man on a white horse.” They sent a stock broker to Europe to study all the fascist shirt-movements, which were dominated by disgruntled WWI vets — like Hitler himself. The plan was to use the 500,000 member American Legion, which was made up of many angry WWI vets. At the time, it outnumbered US military forces. Asked to be that “man on a white horse,” Butler played dumb and took notes, eventually turning the plot over to the House Un-American Activities Committee, HUAC. They held a hearing and the would-be plot was outed by Butler’s testimony. The investigation, however, was minimal and disappointing, and the Wall Street plotters slipped away. FDR likely used the information to hold treason charges over their heads. The story has certainly been kept from our history books.

As to whether it was a real coup attempt outed early by Butler or a slapstick comedy, as some dismiss it, Katz sticks with the facts. And the facts are the investigation was cautious and, in the end, toothless, something that may rhyme quite painfully with some of today’s hearings. Certainly the two impeachments. Had not Butler spilled the beans when he did and had they chosen a true fascist like MacArthur as their man on a white horse, it might have been different.

Butler died from cancer in the Philadelphia Naval Hospital on June 21, 1940.

The Story Ends as Elegy

US imperial history is intricately embedded in our American DNA. So what happens when the bursting-at-the-seams outward imperial pressure reaches a nadir and the nation’s focus becomes one of pulling back? What happens with all that imperial pride that’s so important to so many Americans? Doesn’t it have to go somewhere? All that cruel, bloody militaristic energy expended outward over more than a century and glorified in the pursuit of American greatness and exceptionalism can’t just be allowed to go away. Some of it will surely be directed at places like China that fall into the category of ”the rise of the rest”, former developing “third-world” nations (in China’s case, now an authoritarian behemoth) who’ve become direct competitors to the US in a globalized capitalist market. Some say the world is entering a new, re-shaped colonizing struggle — a new Great Game — given how globalization, tribalism, the rise of authoritarianism and a new realm called cyberspace have made everything much more complicated and nuanced. All war from now on will be cyberwar.

Will some of that frustrated militarist fervor of yore be re-directed internally toward domestic enemies in what some see as a 21st century civil war that rhymes with “the troubles” in Ireland? The enemy will include “Liberals” and others seen as letting the great Empire down. One can see signs of this in a lot of places. There’s the man in my suburban cul-de-sac; he’s a roofer, a pleasant fellow who fixed my roof several years ago. He now sports a large sign in his front yard that declares:

TRUMP

Make Liberals Cry Again

Of course , it’s silly. But it does clearly suggest the taking of sadistic pleasure from “owning” liberals and making them cry. Feeling sad and powerless? Then, kick a liberal; it’ll make you feel much better. One fellow in Idaho was caught on a mike at a municipal meeting asking a politician: “When can we start shooting these people?” They want to censor and even burn books that, they say, make their children uncomfortable or sad. I would not be surprised to see Katz’s book attacked like this, somewhere, as subversive and harmful. They see red when they hear the word dialogue. They’re like that famous Spanish fascist who said: “When I hear the word culture, I reach for my revolver.” They whip up the idea of warrior masculinity to bully the idea of respecting and empowering women and gay people. Insult and intimidation become the drill. They purchase lots of AR15s and AK47s and threaten to show up armed at your next peace and justice demonstration. In Texas and other places, they’re legitimizing and legalizing novel forms of vigilantism. State legislatures are, meanwhile, eating away at the structures of democracy itself. As the hit movie satire Don’t Look Up suggests, a frightening percentage of Americans are modern Know Nothings and proud of it. The white male identity-politics backlash driving this madness seems to come down to this: What do you call an insecure, reactionary, white ignoramus with a gun?

Sir!

They can be guaranteed to always employ some version of the stabbed-in-the-back myth that, in this case, posits liberal weakness as the cause of US decline. Leftists whining about peace and empathy for others are stealing our liberty. Maybe it’s all just bluff and bluster. But, then, could we reach a point where the left and liberal side of our polarized nightmare becomes so resented and so outgunned by the far-right that a sporadic lethal reaction could be seen as a metaphoric variant on Butler’s Marines eliminating poorly armed Cacos fighters from the dialogue? That’s a rhyming turn-of-events with Butler’s era I hope is just paranoid brainstorming.

Katz quotes the historian George Corvington on Butler’s complicated character: “This officer of endurance and indomitable energy, who in his good moments showed himself to be a sparkling conversationalist, had these mood swings that crossed a line and placed him in the ranks of the most vulgar saber rattlers.”

Reading Katz’s book on the horrors of American imperialism reminds me of the closing lines of Joseph Conrad’s famous novel of European colonialism, Heart of Darkness: “The horror! The horror!” The same words find their way into the imperialistic epic of Vietnam, Apocalypse Now. This, of course, is no coincidence, since Vietnam falls into line with the colonial wars Butler was deployed to. Discussions about American imperialism — even the term itself — has been verboten in mainstream venues. That’s because it’s associated so much with leftist ideology. But more to the point, once you raise the lid and honestly look down into the abyss of a career like Butler’s, American Imperialism becomes a morally repugnant, at times quite evil, enterprise. Accordingly, it takes a long time and lots of killing before the horror of it all finally hits the Butler. Then, it’s too late.

Katz tells Butler’s final years as elegy. After the Business Plot, he’s a pariah in the eyes of many. He knows way too much about terrible things consistently kept from the minds of average Americans, who, of course, don’t want to know too much: What they want is comfortable lives. Like a lot of marginalized moral voices in America, Butler publishes essays in socialist magazines; he appears on stage with communists and people like the poet Langston Hughes. Quakers around the country send him letters “demanding (politely)” to know how “an admitted mass killer” can call himself a Quaker in good standing. (The West Chester meeting defended his birthright status.) A communist party leader says this of him, not unsympathetically it would seem:

“[H]e is a simple man. . . . He is just a soldier fighting for the soldiers.”

As Butler’s life comes to a close, he sees his painfully-earned, impassioned moral concerns going nowhere. He finds himself caught in a politically polarized circus that rhymes with the one we’re all caught in today. It’s significant Butler died a year before Pearl Harbor, a fate that freezes his anti-war passions in amber. But I’m with Katz, who feels, after Pearl Harbor, Butler would have given up his anti-war mission and folded himself into the patriotic war effort. If for nothing else, to do right by his beloved soldiers.

But we’ll always have that iconic war-weary Smedley Butler to ponder frozen in amber.

Butler published War Is a Racket, his famous 55-page pamphlet, in 1935. Knowing the long, complicated story Katz tells, the future shadow of WWII does nothing to alter the confessional moral clarity and the personal releasing-from-bondage power of this feisty general’s famous words:

“I served in all commissioned ranks from second lieutenant to Major-General. And during that period I spent most of my time being a high-class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and for the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer for capitalism. I could have taught Al Capone a thing or two.”

As Kurt Vonnegut, who as a POW survived the horrors of the allied bombing of Dresden, would drolly write: “And so it goes.” I think the vulgar, anti-war bantam rooster Butler and the dry, fatalistic master of modern absurdity Vonnegut would have gotten along really well.

[ In the top cover photo, at left, J.P. Morgan in a tophat looking quite predatory among other capitalist land sharks on the hunt for imperial investments and profit centers to be secured by Butler and his Marines, in the photos at the bottom. ]