I met Janet Burroway when I was a Vietnam veteran on the GI Bill at Florida State University and I signed up for a creative writing workshop she was just hired to teach. She was a worldly, published novelist seven years older than me. She had just left an oppressive husband, a Belgian, who was an important theater director in London where she’d been to parties with the likes of Samuel Beckett. I graduate in 1973, and in a turn of events that still amazes me, I asked her out and ended up living with her for a couple years. She had two beautiful boys, Tim, 9, and Toby, 6, who I grew to love.

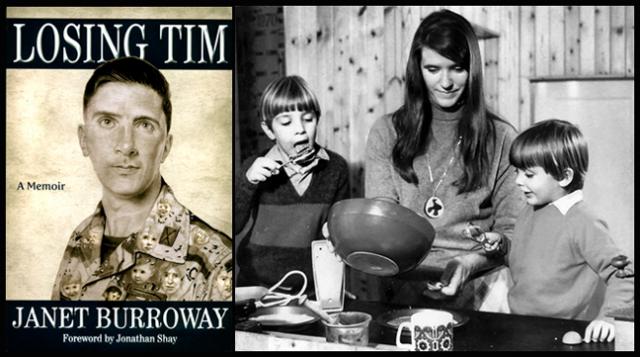

The cover of Losing Tim; and Tim, Janet Burroway and Toby in England circa 1971

The cover of Losing Tim; and Tim, Janet Burroway and Toby in England circa 1971

Cut to 2004. Even as a kid, Tim had a hard-headed moral code about what was right and wrong. As he grew into manhood, he became enamored of all things military; he loved guns. He had a career in the Army as a Ranger, where all his evaluations suggest a stellar soldier. He reached captain, but a promise to his wife and other reasons led him to resign his commission in the active Army. He worked in the Army reserves for a while in places like Bosnia. Contacts led him to civilian jobs in the military contractor world in Africa and Iraq, where he ended up running de-mining operations and training de-miners for RONCO Consulting Corporation.

By Spring 2004, he decided to resign from RONCO. He visited his mother in Tallahassee, then flew to Namibia, northwest of South Africa, to be with his wife Birgett, a white Namibian he’d met during an assignment in Africa where she worked for the UN. Birgett had an adolescent son from a previous relationship. They had a one-year old daughter.

The details are not absolutely clear. Tim was certainly disillusioned from his experiences in Iraq and was apparently sinking into depression. For reasons only he could know, one afternoon he put a nine-millimeter pistol to his head and, in front of Birgett, shot himself dead at age 39.

What is one to make of an act like this? What is a mother to make of the death of her son in this way — especially a mother who throughout her son’s military and contractor career was politically at odds with her son and against the war in Iraq? If that mother is a respected novelist with a talent for spare, honest prose, the answer is a memoir like Losing Tim, just published by Think Piece Press.

For a flavor of the writing in Losing Tim, here’s Burroway on the political tension between her and Tim and how it matured her as a mother:

“Here’s the irony: that nothing led me toward eventual adulthood quite so insistently as the passive endurance of my disappointment — that I had borne, and must adore, a golden right-wing gun-toting soldier son.”

Burroway has published eight novels, as well as plays, essays, poetry, creative writing textbooks and children’s books. Her latest novel Bridge of Sand was published in 2009 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Her novel Raw Silk was just re-issued by Open Road. She’s now at work on a musical adaptation of Barry Unsworth’s novel Morality Play set in medieval Europe and a play about her son Tim. She is the Robert O. Lawton Distinguished Professor Emerita at Florida State University and won the 2014 Lifetime Achievement Award in Writing from the Florida Humanities Council.

Although I’ve not seen any of the Burroway family for 38 years, Tim Eysselinck’s story is personally heart-breaking for me. Like his mother’s inclination in Losing Tim, I can’t divorce his death from the corrupt politics of war in America. I’ve been immersed in the business of soldiers and veterans and post traumatic stress and anti-war politics for the past 35 years. Coincidentally, in December 2003 — the point Tim’s disillusion was growing — I was in Baghdad with a group of antiwar veterans and military family members on a two-week fact-finding trip. We were told by Paul Bremer’s assistant that family members visiting their sons and daughters in a US war zone was unprecedented.

When we got home, I was part of a three-hour press conference on C-SPAN at the Washington Press Club. We talked about how and why the invasion/occupation was a debacle, how a home grown insurgency was on the rise motivated by defense against our troops and how our leadership had betrayed the American people and had handed the nation a dishonest quagmire war.

Janet Burroway in her writing office and Tim Eysselinck with war detritus in Iraq

Janet Burroway in her writing office and Tim Eysselinck with war detritus in Iraq

That was the detached observations of a drop-in journalist. For Tim, it was his whole life. People were beginning to shoot at his team. There were roadside bombs. He mentioned to friends witnessing a disturbing, cavalier attitude toward civilian casualties. During his visit to Tallahassee, Burroway writes, “…he was disillusioned with the Bush administration and the Paul Bremer regime. … He seethed: the corruption, the incompetence, the lies, the greed, the stupidity!” (Italics in original) At one point he says, “I’m ashamed of being an American.” He later says to his wife, “I’m tired of being the bad man.”

Burroway quotes David Hume: “Suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem.”

In a disgraceful hearing over post-suicide benefits for Tim’s family, RONCO attorneys argued that Tim didn’t suffer from Post Traumatic Stress. The corporate lawyers diminished their dead employee in any way they could to avoid paying money. They suggesting the de-mining work in Iraq was not dangerous and that Tim had never experienced combat or seen anything unpleasant. The Houston judge laid down for RONCO.

This kind of profit-focused, corporate dishonesty and lawyerly manipulation is, in fact, the real problem. The Iraq War was a great shining moment for corporate/finance war profiteers like Dick Cheney. Military tasks were privatized, which meant they became morally unaccountable profit centers that fell outside the public radar. Privatized war employees were/are, it’s true, well paid, but more important they became unseen and expendable. In such a cold-blooded, bottom-line oriented world, an employee’s PTSD diagnosis becomes something for lawyers to argue ad-nauseum into meaninglessness.

What Tim Eysselinck suffered from is called a “moral wound” that, in his case, ended up being fatal. Take a highly moral, idealistic young man with dreams of doing good in the world and set him down in a moral cesspool of corruption like the Iraq Occupation under Henry Kissinger protégé Paul Bremer and you have all the ingredients for a festering psychic wound. In Tim’s case, in a moment of family stress and weakness, he snapped.

In her 2007 book, The Shock Doctrine, Naomi Klein writes about “disaster capitalism.” She traces her idea to the thinking of conservative economist Milton Friedman, who wrote, “only a crisis — actual or perceived — produces real change.” The most natural and logical extension of this thinking is, if there is no crisis to catalyze the change you want, you induce a crisis. In Iraq, “shock and awe” threw that small nation into a state of shock. Even the Viet Minh when they beat the French kept the French governing structures in place. Instead, the Bremer gang absolutely dissolved the existing Bath Party political structure and disbanded the entire Iraq army. It’s akin to the basic training idea of breaking a young man down completely, then building him back up as you want him to be. “Next came the radical economic shock therapy,” Klein writes, “imposed while the country was still in flames.” This shock therapy was unfolding in late 2003, early 2004, the point Tim was wrestling with disillusion.

In an introduction to Losing Tim, Jonathon Shay, author of Achilles in Vietnam, writes, “Moral injury occurs when there is a betrayal of what’s right in a high stakes situation by someone in legitimate authority.” (Italics in original) That’s the Iraq War in a nutshell, though with the 2000 election we might quibble over the adjective “legitimate.” Dishonest leadership inexorably leads to moral casualties, especially in a context where leadership has so cynically unleashed the dogs of war. I submit the only way a young man like Tim Eysselinck could have avoided his fateful disillusion is if he had been more of a sociopath, in which case he might have thrived.

The power of Burroway’s spare memoir is in her determination not to indulge in hand-wringing pathos or to worship the idea of the fallen “warrior.” Her grief is of the order found in Greek tragedy. And like all classic tragedy, the final tragic act hinges on decisions made by the protagonist. Whether seen as a thought-out conscious act or as an irrational momentary impulse — in Tim’s case it’s impossible to be certain — shooting himself was Tim’s decision based on a complex and ambiguous web of factors. Burroway does her best to peel back these layers of the onion. Like the good imaginative writer she is, she even envisions Tim having too-late second thoughts in the final milliseconds of his act.

By the end of the memoir, we know an awful lot about Tim and the Burroway family, but we have not gained any absolute certainty about his suicide. The point is, no one will ever know for certain why Tim Eysselinck, a man seemingly on top of the world, decided to shoot himself.

Burroway would like to see greater awareness for the conundrums of the private contractor. Beyond the good salaries, for-profit corporations have no social incentive to place any greater value on their lives. William Langewiesche wrote about this in an April Vanity Fair article called “The Chaos Company” about G4S, a huge corporation headquartered in London that contracts for de-mining and other military and security tasks. Langewiesche says, while the majority of its employees are unarmed, G4S is three-times the size of the British military and generates $12 billion in revenue a year. “Enterprises such as G4S are now a part of the international order, more permanent than some nation-states, more wealthy than many, more efficient than most.” The growth of western civilian contractors in war zones around the world can be seen as another sign of the break-down of the nation-state system into global networks of power. At the point of this spear is the secret world of surveillance, special operations and cyber warfare.

The evidence is indisputable that the rich keep getting richer and the poor poorer in the United States. There seems little relief in sight for this reality. The nation’s much-vaunted middle class is shrinking. Workers’ unions have been crushed. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court and other institutions keep firming up the foundations of this social Darwinian dynamic. The free market is sacred and profit always matters most. The notion that people might be motivated by ethics and social concerns other than money gets lost in the hoopla or is dismissed as naïve.

I see an idealistic Tim Eysselinck — like many, a man on a perennial search for good fatherly authority — running head-on into the corrupt capital-obsessed cesspool that was the war zone called Iraq.

But that’s my reading. Burroway knows absolute certainty is the stuff out of which wars are made. Her book is more art than polemic. In an epigram, she quotes Anne Carson: “In every story I tell comes a point where I can see no further.” Still, she does not shy from making an eloquent cry from the heart advocating for humanity and compassion as a trump to the kind of rigid militarist thinking that led to her son’s suicide. She closes the book by telling us that — as I’ve heard combat veterans say of dead comrades — she still talks with Tim.

“Tim is no further from me than he was in Africa, and in some ways nearer. …I make him up.” She takes comfort in the legacy of his clearing mines: “…all over the world is a slender web in space and time, of people whose lives were changed, or who were born at all, because my son who loved weapons went, by the hazard of history, into the odd profession of getting rid of them.”