Mumia Abu-Jamal, the prison journalist long known as the “voice of the voiceless” for his compelling writings and short audio tapes about life behind bars, moved a step closer to getting a chance for a reconsideration of his earliest appeal of his conviction — an allegedly flawed Post-Conviction Relief Act hearing in 1995, as well as three other later PCRA appeals of aspects his case, all ignored and their findings rejected by Pennsylvania’s appellate courts under spurious conditions.

The opening comes in the form of dismissal by the state’s Supreme Court of an attempt by Maureen Faulkner, widow of slain Philadelphia Police Officer Daniel Faulkner, to use an obscure legal gambit called a King’s Bench petition, to have DA Larry Krasner’s office removed as the legal entity defending against Abu-Jamal’s appeals. That effort, filed last February had blocked any forward action on those appeals.

Abu-Jamal’s attorneys had filed an appeal several years ago in Philadelphia’s Court of Common Pleas, claiming that the handling of those four PCRA hearings, all of which were rejected by the State Supreme Court, were all constitutionally flawed because one of the judges reviewing them, Justice and eventually Chief Justice Ronald D. Castille (now retired), had refused Abu-Jamal’s requests that he recuse himself, despite his having been Philadelphia’s district attorney and the man overseeing the DA Office’s legal effort to oppose Abu-Jamal’s appeals of his sentence and conviction. (That appeal was filed following the discovery of two notes — a draft letter and a final letter by then DA Castille to then Gov. Tom Ridge in 1990 calling on Ridge to speed up the signing of execution warrants for convicted “police killers” in which Castille said such a measure would “send a message” to would be police killers.

The appeal also came following a 2016 US Supreme Court ruling in a case called Williams v. Pennsylvania, in which another Philadelphia defendant convicted of murder sentenced to death was granted a new penalty phase trial because the same Justice Castile had as DA approved his prosecutor seeking the death penalty, and then did not agree to recuse himself in considering an appeal of that sentence.

Abu-Jamal’s new legal effort gained urgency when in late December 2018, newly elected progressive DA Krasner (elected in Nov. 2017), reported discovering, in an unused storeroom of the DA’s office, six file boxes containing a vast number of documents relating to Abu-Jamal’s case. Many of these documents were found to be dated from around the time of his 1982 trial, and including material that should, under the US Supreme Court’s 1963 Brady decision, have been disclosed by to Abu-Jamal and his defense team at the time of the trial or, depending on the date of their production, before his 1995 PCRA hearing.

Among these documents was, for example, a shocking letter from a key prosecution witness, a young white taxi driver Robert Chobert, asking prosecuting attorney Joseph McGill, “Where is my money?” As journalist Linn Washington has noted, Chobert, as a prosecution witness, was unlikely to have been asking for reimbursement for travel to court, or for meals as a witness, “Because typically as a key prosecution witness he would have been brought to and from court by police officers, and would have been provided with his meals and hotel room by the DA’s office, not expected to front his expenses himself and then get reimbursed.”

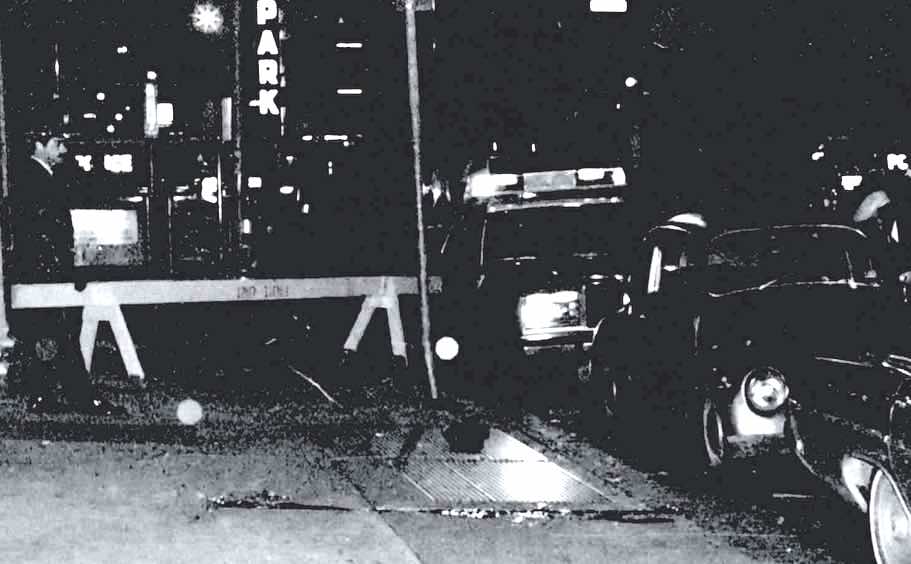

Chobert was indeed a critical prosecution witness, as he claimed at the trial to have parked his taxi directly behind Faulkner’s patrol car, and that from that position to have witnessed Abu-Jamal allegedly firing multiple times down at the prone Faulkner on the sidewalk with his licensed snub-nosed pistol. That testimony has been challenged by many because photos of the crime scene taken almost immediately after the shooting do not show a taxi cab behind Faulkner’s squad car. Also many people familiar with this case, this journalist included, find it hard to believe that Chobert, who at the time was driving his taxi cab illegally because his license had been revoked following a DWI conviction, and who moreover, was also at the time on probation on a five-year sentence for felony arson of an elementary school, would have pulled up and parked directly behind a cop car.

(In fact, it is likely that Chobert was actually parked a block away on 13th street north of Locust where the shooting incident occurred, his vehicle pointing away from the scene. This would explain why no other witness, for either prosecution or defense, ever mentioned either in court testimony or in statements to police investigators seeing a taxi cab near Faulkner’s car or the shooting, and why the other main eye witness, the prostitute Cynthia White, in a drawing she made of the scene for police detectives, drew Faulkner’s car, Abu-Jamal’s brother’s VW in front of it, and even an uninvolved Ford sedan in front of that, but no taxi.)

The idea that there was a letter from Chobert asking the DA for “my money” that was not provided to the defense between his 1982 trial and the time when Chobert was recalled to testify at the 1995 PCRA, is certainly appalling. It appears on its face to be a serious case of probable prosecutorial misconduct, or the type of evidence that, if known of to a jury considering a murder conviction, could have led to a different outcome. (Jury decisions in felony cases have to be unanimous for conviction, so even one juror voting no to conviction makes it a hung trial.)

Also important in those discovered boxes were other documents further suggesting that Judge Castille, while DA, contrary to his own assertion, was indeed directly monitoring not only the disposition of his office’s death penalty cases, but how his office’s felony appeals unit was handling the legal effort to oppose Abu-Jamal’s appeals as they moved up through the state’s court system.

Common Pleas Judge Leon Tucker disagreed with Castille’s decision on recusal in the Supreme Court’s consideration of Abu-Jamal’s various PCRA hearings. In supporting Abu-Jamal’s motion to have four of his rejected PCRA hearings re-considered, or reopened, because of Justice Castille’s failure to recuse, he cited the US Supreme Court’s Williams precedent. In that 2016 precedent-setting decision, the US Supreme Court ordered a new sentencing jury trial for the convicted and condemned Terrance Williams, finding that the same Justice Castille’s refusal to recuse himself after having as DA approved a subordinate prosecutor’s request to seek the death penalty, had “violated the Due Process Clause of the [US Constitution’s] Fourteenth Amendment.”

Using forceful language, the Judge Tucker wrote, regarding Abu-Jamal’s petition:

“The claim of bias, prejudice and refusal of former Justice Castille to recuse himself is worthy of consideration as true justice must be completely just without even a hint of partiality, lack of integrity or impropriety.”

Tucker added, citing the US High Court’s Williams ruling:

“If a judge served as prosecutor and then the judge, there is a finding of automatic bias and a due process violation…The court finds that recusal by Justice Castille would have been appropriate to ensure the neutrality of the judicial process in [Abu-Jamal’s appeals] before the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.”

The ruling by Tucker (the first African American jurist to have heard any aspect of the Abu-Jamal case or any of his appeals over four decades), was properly viewed (including by the widow Faulkner and the Philadelphia Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) as a stunning breakthrough, offering Abu-Jamal, for the first time in more than two decades, an opportunity to have his conviction, not just his now-vacated death sentence, reconsidered.

But that appeal was halted in its tracks earlier this year when Maureen Faulkner, the widow of the slain Officer Daniel Faulkner, backed by the FOP, filed in Supreme Court a rarely used King’s Bench petition — a hoary legal maneuver dating to pre-Revolutionary British Common Law — arguing that DA Krasner, a progressive former defense attorney who won election as DA in November 2017, was prejudiced in favor of Abu-Jamal and should be barred from defending against his appeal petition. Faulkner’s King’s Bench petition made a number of factually erroneous or baseless claims that Krasner had a pro-Abu-Jamal bias. Her attorney, George Bochetto, made nine claims to support his client’s contention about Krasner.

Among these were the assertion that the new progressive DA had been a member of the National Lawyer’s Guild, a civil rights organization of mostly leftist activist atorneys, some of whose Philadelphia chapter members in 2000 had defended protesters at the 2000 Republican National Convention in Philadelphia, calling for Abu-Jamal’s freedom; that Krasner had publicly referred to “some prosecutors” in the DA’s office as being “war criminals;” and that he had not tried to challenge or delay Judge Tucker’s order authorizing a new PCRA to consider the cartons of hidden and unreported documents relating to Abu-Jamal’s case.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court on Dec. 16, in a in a 3-1 ruling (signed by Justices Christine Donohue, David Wecht and Kevin Dougherty, with Justice Sallie Updike Mundy dissenting and three justices who had sat on the Supreme Court with Justice Castile recusing themselves because of a real or perceived conflict of interest) , supported the conclusion of that court’s appointed “master,” McKean County Judge John M. Cleland. Judge Cleland, after a lengthy and detailed investigation at the request of the court that included interviews with Krasner and other witnesses, had recommended rejection of the King’s Bench petition. He reported that he’d found no “direct evidence of a conflict of interest” or even “an appearance of impropriety” that would “compromise” DA Krasner’s ability to “carry out his responsibilities,” in defending against Abu-Jamal’s appeal of his PCRA rejections. The court master learned for example that Krasner had never paid dues to be a member of the NLG and in any event was not personally involved in defending any pro-Mumia protesters arrested at the convention. He said he found other Faulkner claims regarding Krasner bias to be similarly without any factual basis.

As Judge Cleland concluded in his report to the court:

“A perception based on the arguments of detractors cannot overcome the actual and undisputed fact that Ms. Faulkner has presented no evidence that Krasner or his assistants have not defended the conviction of Mumia Abu-Jamal or do not intend to do so in the future.”

He added:

“No credible argument has been made that Krasner and his assistants have adopted legal positions or legal strategies that do not have arguable merit or are not supported in law based on the facts.”

Abu-Jamal Attorney Judy Ritter tells ThisCantBeHappening!, “The King’s Bench petition has been dismissed, and that decision cannot be appealed. Now our case involving the four rejected PCRA hearings can go forward.”

So too will the long-delayed evidentiary hearing into the contents of those six boxes of prosecutorial documents relating to the case — documents that prior DAs from Ed Rendell through Ron Castille, Lynn Abraham, Seth Williams to Kelly Hodge had illegally kept undeclared and hidden away from Abu-Jamal and his lawyers for four decades.

What happens next will be a hearing before a superior court panel on Abu-Jamal’s petition for reconsideration of his PCRAs into whether the newly discovered documents pose a Brady violation in his initial trial or later during his PCEA hearings. That panel can make a determination, refer the case to a Superior Court judge, or decide to move everything directly to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court — a court that will no longer have the controversial Justice Castille, now retired, sitting on it.

Abu-Jamal’s appeal prospects in that court could be iffy, given the recusal already in the current case by three of the court’s seven judges, and by negative comments about the applicability of the Supreme Court’s Williams precedent to Abu-Jamal’s case filed by on of the three judges who concurred in the 3-1 decision, not to mention the dissent by one judge. (Pennsylvania’s higher courts have been notorious for showing a proclivity for denying this particular prisoner, Abu-Jamal, the benefits of precedents routinely made available to less notorious appellants — a point specifically noted by Judge Thomas Ambro, one of the three federal Circuit Court judges who heard his last appeal of his conviction, and who dissented when that panel voted 2-1 to uphold his murder conviction, saying “I don’t see why this appellant isn’t afforded the benefit of the same precedents as other appellants.”)

With only four current justices able to consider Abu-Jamal’s case at present, two of whom have expressed their opposition to the appeal already (Dougherty in a critical concurrent opinion and Mundy by her dissent in the King’s Bench petition), there would be a potential for a tie vote, which would leave any superior court order standing. Though given the time the appeals process takes, it is also likely that Chief Justice Saylor, a Castille court era holdover, whose will be leaving the court at the end of his term next year, will have been replaced by a fifth Justice who could participate in any ruling. (The Supreme Court can also appoint a temporary lower court judge to sit in judgement on a case if there is a danger of a tie because of recusals or other absences from the bench.)

That said, one of the justices who voted with the majority of the state Supreme Court to reject Faulkner’s petition, David Wecht, wrote a powerful 20-page concurring opinion supporting the court’s King’s Bench petition rejection. In that concurrence, he included a blistering dismissal of the negative comments about DA Krasner and Abu-Jamal’s case made by his court colleague Justice Kevin Dougherty, writing:

The dearth of evidence in the record to support Ms. Faulkner’s allegations does not deter my learned colleague, Justice Dougherty, with whose perspective I respectfully disagree. Justice Dougherty elects to forego the requirement that we afford supported factual findings due consideration and chooses instead to ignore those findings and reach his own conclusions. Notwithstanding the broad prerogatives attendant to our review at King’s Bench, this approach strikes me here as unwise and in any event unavailing. It is axiomatic that we afford due consideration to fact-finders, because ‘the jurist who presided over the hearings was in the best position to determine the facts.” I see no reason not to give Judge Cleland’s findings their due “‘consideration.’”

After several pages devoted to a thorough debunking of Dougherty’s evidence-free claims of purporting to demonstrate Krasner’s pro-Mumia bias, Wecht writes:

‘”From that empty bucket, Justice Dougherty somehow nonetheless finds paint to compose a ‘disturbing picture.’ However vast our authority in cases such as this one is, our standard of review still does not permit such creations.”

Justice Wecht also debunks, in his concurring opinion, the arguments of Justice Mundy, the lone dissenter to the decision rejecting Faulkner’s King’s Bench petition, writing:

“Justice Mundy’s dissent fares no better. Like Justice Dougherty, Justice Mundy elects to premise her analysis upon Ms. Faulkner’s allegations, ignoring the fact record as it now stands and the decisions that Judge Cleland made based upon that record. As opposed to Justice Dougherty, Justice Mundy would resolve the matter [regarding Abu-Jamal’s right to appeal for a reconsideration of four PCRA’s where Judge Tucker found Justice Castille should have recused himself] instead of awaiting a future ruling based upon Reid. However, like Justice Dougherty, Justice Mundy makes no serious attempt to explain if, or how, Judge Cleland’s fact-finding was undeserving of our due consideration. Consequently, Justice Mundy’s position fails for the same reasons that undercut the position advanced by Justice Dougherty.”

Since 2001 when his death sentence was finally ruled unconstitutional and converted to a sentence of life without chance of parole, Abu-Jamal has spent nearly 20 additional years in prison, some of that time still held in solitary confinement on the state’s death row while the DA battled all the way to the US Supreme Court trying unsuccessfully to have his death sentence reinstated. Now 66, he is suffering from cirrhosis of the liver from a Hepatitis C infection contracted while in prison and left untreated for some time until he won a federal lawsuit mandating that effective treatment be belatedly made available to him. Over the years, Abu-Jamal, referred to by supporters and opponents alike by his first name Mumia, has been the focus of intense efforts by the Philadelphia FOP, which, along with Faulkner’s widow, has campaigned doggedly since his murder conviction to have him executed, and, since his death sentence was overturned on Constitutional grounds, to keep him locked up and denied avenues of appeal.

Meanwhile, a global campaign seeking his freedom continues to demand his release from prison, arguing that he never received a fair trial and that, as he has always maintained, he did not murder Officer Faulkner.

That Abu-Jamal did not receive a fair trial is clear given how the trial judge, the late Albert Sabo, a jurist notorious for having both the greatest number of death penalty notches on his belt of any jurist in the US, and the most convictions and death sentences overturned on appeal, repeatedly denied defense requests for subpoenas and witnesses, and allowed the prosecutor, in his summation to the jury, to make spurious references to Abu-Jamal’s having been a member of the Black Panther Party as a 15-year-old kid.

That Abu-Jamal didn’t receive a fair appeal process is even clearer. First there’s the fact that Judge Sabo was controversially recalled from retirement to preside over Abu-Jamal’s initial PCRA, where he was being asked to rule on claims about his own decisions as a judge at the original trial. In that PCRA, Sabo proved so biased in his rulings on things like permissible testimony and requests for subpoenas of witnesses that even the Philadelphia Inquirer, no backer of Abu-Jamal, editorialized calling the judge’s behavior at the hearing “embarrassing.”

The corruption of that case has been made even more abundantly clear by Judge Tucker’s comments on Castille’s failure to recuse himself in the Supreme Court’s ruling on Abu-Jamal’s PCRAs, and by the recent discovery of the hidden crates of prosecution documents in the DA’s office that were never revealed to the defense in the case.

The existence of those documents in themselves is a clear violation of the US Supreme Court’s 1963 Brady policy, which requires that prosecutors provide defendants in criminal cases with all evidence in their possession that might conceivably help exonerate a defendant.

Whatever the future holds, this case is not going away, and Abu-Jamal and his defense team are headed, finally, to a Pennsylvania superior court hearing on Judge Tucker’s ruling granting Abu-Jamal the right to challenge the earlier rejection of his PCRA hearing findings by Pennsylvania’s higher appellate courts. Beyond that, should the appeal for reconsideration of his four rejected PCRA’s and for the chance to have a further PCRA hearing on the new evidence that could challenge his conviction be rejected, he could — though over the years the Congress and the US Supreme Court have made it increasingly difficult — have an opportunity to bring his case back into federal court with a second habeas petition.

DAVE LINDORFF, author of “Killing Time: An Investigation into the Death Penalty Case of Mumia Abu-Jamal” (Common Courage Press, 2003)