The past two days were a roller-coaster for me in the national struggle for meaning in the realm of war and peace. First, I was talking with a friend about his conscientious objector status specifically to the Vietnam War. This was early in the war, and he made it under the wire. Soon, draft boards realized they better stop giving CO status to those morally opposing a specific war, lest they encourage a groundswell of opposition among potential combatants that could undermine an unpopular war like the one the US government chose to unleash on the Vietnamese. The war really began in 1945 when President Truman betrayed our WWII ally, the Vietnamese, and supported re-colonization by the French.

Senator John McCain and documentary filmmaker Ken Burns

Senator John McCain and documentary filmmaker Ken Burns

Later that night, I was part of an hour-long group phone call of fellow Vietnam veterans and friends in an organization called Full Disclosure. The group works to counter the government’s well-funded 13-year propaganda project to clean up the image of the Vietnam War; it emphasizes individual heroism and passes out badges and plaques to veterans. Members of Full Disclosure are very concerned right now about the upcoming Ken Burns 10-week PBS documentary series on the Vietnam War. Trying to get any kind of influence with Burns or members of his team on how the war is to be represented to Americans in 2017 is an uphill struggle.

Following the Full Disclosure phone call, I watched Mel Gibson’s excruciating film Hacksaw Ridge, about a CO medic who refused to even touch a rifle and saved 75 men from certain death in a horrific battle on the island of Okinawa in May 1945. I find Mel Gibson to be a repugnant lout; but my CO friend told me the film was a must-see. The husband of a gay Vietnam veteran friend who was a Navy corpsman with a Marine infantry unit in Vietnam also told me the film was good and how it reminded him of his husband’s experiences in Vietnam. (My medic friend felt no need to personally sit through Gibson’s gore fest.) Like the protagonist of Hacksaw Ridge, my friend refused to carry a weapon and saved men with sucking chest wounds and mangled and bleeding legs. He had been assured by a Navy recruiter he would be sent to journalism school, but Navy leaders did not need young men to assemble facts and information on the war; they needed what is historically known as cannon fodder, specifically cannon fodder able to keep other men alive. As cannon fodder, my friend’s sexual preference was irrelevant.

While Hacksaw Ridge suffers from Gibson’s aesthetic psychosis for wrenching agony and gore, this doesn’t overwhelm the story of Virginia pacifist Desmond Doss who, along with his brother and mother, was regularly beaten by his drunken father. The father is a WWI veteran suffering a harrowing case of PTSD. One of the marvels of the film is how we’re made to sympathize with this bastard, played by Australian actor Hugo Weaving. In a key scene, Desmond (Andrew Garfield) comes very close to actually shooting his father for beating up his mother, but instead declares he will never touch a firearm again. The movie is about how Doss adjusts to the military towards the end of the war. He eventually earns a Congressional Medal of Honor. Gibson does broach new ground for a war film in American pop culture; in the eras of John Wayne and Clint Eastwood, a determined pacifist as hero/protagonist would have been unthinkable. Some may recall Gary Cooper as a Tennessee pacifist in the military in the 1941 film Sergeant York; York overcomes his character shortcoming to become a sharpshooter who kills dozens of Germans. This was the popular message in 1941.

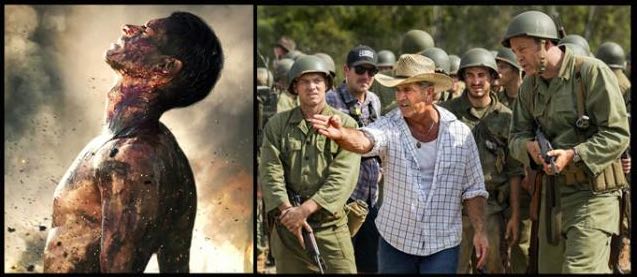

Andrew Garfield as Desmond Doss and Mel Gibson with actors on the set of 'Hacksaw Ridge'es to advance our national interest.” McCain goes on at great length on how “exceptional” the US is and how great our “values” are. We are a nation “distinct from all others in our achievement, our identity and our enduring influence on mankind. Our values are central to all three.” The assumption is that our values are always morally exceptional and the world reveres us for it.

Andrew Garfield as Desmond Doss and Mel Gibson with actors on the set of 'Hacksaw Ridge'es to advance our national interest.” McCain goes on at great length on how “exceptional” the US is and how great our “values” are. We are a nation “distinct from all others in our achievement, our identity and our enduring influence on mankind. Our values are central to all three.” The assumption is that our values are always morally exceptional and the world reveres us for it.

This is the Age of Trump, and I do appreciate a good line of bullshit as much as the next guy. We’re all assaulted and overwhelmed by so much information from all quarters that material like the McCain op-ed is how we establish meaning in this bizarre culture — especially in the upper reaches of society where the decisions on war and peace are made. Facts and truth are overrated. Son and grandson of famous admirals, John McCain and his POW story have become iconic; the man functions as a flesh-and-blood Mount Rushmore figure. So he can say virtually anything and have credence.

The trouble is — and this is why his op-ed is insidious — it’s all emotional platitudes that pollsters know resonate with much of the public. An open-minded, honest reading of the history of the Vietnam War, where McCain earned his iconic status, does not bear out the image of the United States as a beacon of moral values. Sure, the United States has a lot going for it, and I’m glad to stand up for the good things. When and where actually applied, the Constitution and Bill of Rights are magnificent documents. But it’s dishonest or naïve to suggest the rights they provide and the justice that’s possible under them is available to everyone; as all honest Americans know, those without power must fight very hard and have significant financial resources to obtain the justice ballyhooed in the Constitution.

McCain starts his paean to American exceptionalism by citing Ronald Reagan for supporting Soviet dissidents and, as governor of California, for supporting POWs like himself in Vietnam. Governor Reagan “had often defended our cause, demanded our humane treatment and encouraged Americans not to forget us.” You’d think Reagan stood courageously alone for POWs. First off, the antiwar movement (even Jane Fonda) never did not “support” American POWs. Though it’s done all the time, it’s counter-intuitive nonsense to suggest the antiwar left had anything to do with causing war casualties or making life difficult for POWs in Vietnam. The left never wanted the war in the first place and fought valiantly to stop it and get our POWs home. It may be the most exasperating attack on the antiwar movement. It’s a no-brainer that it was those who manufactured the war and prosecuted it long after it was deemed unwinnable who caused all the casualties and kept the POWs in captivity so long. And that would include Ronald Reagan.

I spent a fair amount of time as a photographer in Central America during the Reagan years. So Ronald Reagan as a giant for moral values and human rights is a bit much. I heard too many harrowing stories of death squad victims in El Salvador and in the Contra War in Nicaragua to not realize Reagan’s moral “values” in these instances was entirely politically oriented. The syllogism went something like this: We’re fighting communism. Poor central Americans are communists. So killing Central American peasants is good. Or as a Marine acquaintance of mine used to put it: “Kill a Commie for Mommy.” Reagan literally defended people who were torturing peasants in El Salvador and murdering citizens in Nicaragua. He got away with it because it was out of sight, out of mind. What kind of American values does this represent? The answer is, the same values that led to the genocide of the American Indian. We can talk about the Jewish holocaust in Germany and Poland, but we can’t talk about the holocaust of Native Americans in America. It’s the great American value called forgetting or looking the other way.

Everything depends on whose ox is gored, how loud a victim class’ megaphone is and, of course, whether the exceptional American media and the people glued to it like sheep are curious enough to want to know about something. Donald Trump and Rex Tillerson are not unusual in that they coldly base American policy on what they deem to be the American interest. John McCain certainly understands this. In his op-ed, he’s simply initiating an insider pissing contest with the Trump administration, hoping to gain the Republican high ground. It’s true that Trump and company may be more elitist and ruthless than McCain in the pursuit of their American interest. But that doesn’t alter the fact McCain’s op-ed is a raft of platitudes and patriotic bullshit.

Ken Burns and The Vietnam War

In light of all this talk about values and meaning focused on the Vietnam War, in anticipation of the upcoming Ken Burns’ PBS documentary series on that war, the normal assumptions should be suspended and a serious set of questions should be raised and set loose over America like a hovering cloud of critical thought:

What was the Vietnam War really about? Why was it necessary? Did it accomplish anything at all except death, destruction and disunity in America? Is it possible to fairly account for the suffering and courage of US soldiers (like McCain) caught up in such a morally questionable war without glorifying the war itself? Is it possible for Americans to discuss the war without relinquishing the moral questions? How do such moral questions undermine the traditional line about exceptionalism and patriotism found in John McCain’s op-ed? Is it time to revise that line of thinking for a better future?

I hate to be cynical, but after 40 years of post-Vietnam experience in the antiwar movement I find it hard to conceive of the US government and mainstream media outlets like PBS assuming a position that declares the brutal war against Vietnam “immoral” or “criminal.” At best, it will be treated as a tragic, but honorable, mistake, a painful and controversial period in US history that left a difficult legacy all Americans still live with.

There are many voices that say the war could have been won. (I’d put them in with Sylvester Stallone and the Rambo view of Vietnam.) As even Robert McNamara understood in the mid-1960s, the effort was doomed from the start. Ward Just got it right when he wrote: “The Vietnamese would have fought us for a thousand years.” There’s no doubt some voices will say we actually won the war, since Vietnam is now an Asian capitalist miracle. But, then, there’s the voices that will point out how Ho Chi Minh and his Viet Minh guerrillas were US allies during World War Two and actually loved Americans and wanted to emulate us. In 1945, they literally quoted our Declaration of Independence in their declaration, hoping the US would support their independence against the French who wanted to re-colonize the place after being broken and humiliated by the Japanese.

But it was no deal. Roosevelt might have done it differently. But he was gone. Cold War hysteria ruled in the Truman White House. Vietnam was doomed to suffer 30 years of death and destruction from the most powerful nation in the world. It’s true, the Vietnamese were not softies; they could dish out violence in their own fashion just as well as we could. They suffered much, much more than we did, and they did it more gracefully.

I was quite aware how violent the Vietnamese were when I was a 19-year-old radio direction finder trying to locate young Vietnamese radio operators — men intent on killing me! — in the mountains west of Pleiku. The fact is, like most of my comrades, I was clueless about what was really going on. Using myself as an example, I’ve asked am I willing or able to relinquish any sense of honor about such a vital episode in my young life? Compared to many others, I had it relatively easy. I saw examples of courage in Vietnam. The most courageous thing I did was intercede when I encountered a frustrated, drunken infantryman shooting up a bar filled with terrified prostitutes. In his drunken state, he thought I was an officer, something I took advantage of. I don’t delude myself that this fellow was prevented from any future excesses of violence. I was a kid and part of a massive army. We were like the worst American tourists; instead of cameras, we had loaded guns and a sense of power that often included the power of life and death. That’s a lot to put in the mind of a 19-year-old male. When someone tells me “Thanks for your service,” I always say, “I don’t want to be thanked for my service; I want to be thanked for learning something from my service.”

How exactly the documentary wunderkind Ken Burns treats the overarching moral issues relevant to Vietnam is something on the minds of all members of Full Disclosure. Will he succumb to the flagrant avoidance of moral self-criticism exhibited in the McCain op-ed? Probably not. As is his inclination, he will tell many stories through compelling human artifacts and voices. He’ll no doubt concede the war was controversial. Presumably he will be fair, complete and won’t cheap-shot the real story of the antiwar movement, including civilians and veterans. That also goes for the important Vietnamese side of the story.

Burns has said he can’t make a “blanket statement of judgment on the war.” For me, that’s dangerously close to a blanket statement. As a writer/journalist, I’ve run into this state-of-mind since my first job on a newspaper and throughout my career. It’s called moral accommodation for the sake of access, popularity, sales or getting published at all. This is very much an American value. Mark Twain famously made such accommodations with Huckleberry Finn. The first third of the classic is morally courageous, even revolutionary. Then he puts the manuscript up for years, not sure where he wants to go with it. He wants to make money from the selling of his work, so he establishes his own publishing company. He finishes the book with a middle third of wonderful satiric incident along the river. Then there’s the disastrous third section where he inserts Tom Sawyer, and Nigger Jim is relegated to a chicken coop, where he’s more Step’n Fetchit than the full man and surrogate father of Huck he was in the beginning. Clint Eastwood did it with The Unforgiven, a would-be raw and honest telling of killing in the west that ends with an absurd gunfight right out of the spaghetti western mode. The movie was very popular.

Herman Melville, on the other hand, didn’t accommodate to popular morality. After initial sales of 2,300 books, for the rest of his life Moby Dick sold 27 copies a year. Melville had to get a job as a customs inspector in New York to support his family. His magnum opus was out of print when he died.

To paraphrase H. Rap Brown on violence, moral accommodation in the popular culture realm is as American as cherry pie.