A Philadelphia judge has issued a stunningly powerful order requiring the city’s District Attorney’s Office to locate and release all documents related to the involvement of a former top prosecutor in the most contentious murder case in Philadelphia’s history. Because that former DA, Ronald Castille later became- a state supreme court justice and ultimately chief justice, the order could shine a light onto the dark legacy of ethics shredding misconduct by members of the state’s highest court.

It also opens the door a crack to the possibility that Mumia Abu-Jamal, currently serving a life sentence without possibility of parole, could have his 1982 murder conviction for the killing of a white Philadelphia police officer overturned.

The order, issued recently by Common Pleas Judge Leon Tucker, comes in an appeal filed by attorneys for celebrated jailhouse journalist Abu-Jamal. It represents yet another setback for the Philadelphia’s District Attorneys Office, an office already reeling from federal corruption charges filed recently against the city’s current DA Seth Williams.

Philadelphia prosecutors have spent decades fighting to sustain Abu-Jamal’s murder conviction for the 1981 shooting death Philadelphia police officer, Daniel Faulkner. Since Abu-Jamal’s conviction by a mostly white jury in 1982, entities as diverse as Amnesty International, government officials in the U.S and abroad plus prominent individuals around the world have condemned his trial, conviction and appeals process as a miscarriage of justice fraught with misconduct by prosecutors and judges, including members of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court.

The current Abu-Jamal appeal centers on the legal unfairness of actions taken by former Philadelphia DA Castille, who as top prosecutor, oversaw the legal effort to keep Abu-Jamal on Pennsylvania’s death row, and then later served as a state Supreme Court justice ruling on appeals of those very actions by his former office.

Years after his election to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania in 1993, Castille joined six other court justices in rejecting an appeal by Abu-Jamal for a new trial based on documented evidence of egregious misconduct by police, prosecutors and the judge who presided over Abu-Jamal’s original 1982 trial and over his initial Post Conviction Relief Act hearing in 1995.

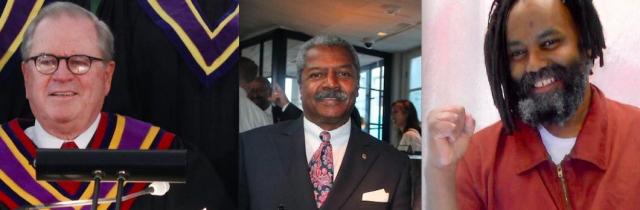

Retired PA Supreme Court Chief Justice Ronald Castille, Philadelphia Common Please Judge Leon Tucker and Mumia Abu-Jamal

Retired PA Supreme Court Chief Justice Ronald Castille, Philadelphia Common Please Judge Leon Tucker and Mumia Abu-Jamal

Abu-Jamal’s legal team recently argued that Castille’s vote in the court’s 1998 rejection of their client’s appeal violated ethics provisions covering all judges in Pennsylvania –- a basic legal rights issue brushed aside by Pennsylvania’s high court in its unanimous 1998 ruling.

This latest Abu-Jamal appeal centers on a 2016 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court in Williams v. Pennsylvania granting convicted murderer Terrance Williams a new trial because of Justice Castille’s refusal to recuse himself from a decision on Williams’ appeal of his conviction. The U.S. Supreme Court in that case blasted Castille because he had, as DA, approved the decision to seek the death penalty against Williams. His later vote as the state’s top judge denying an appeal of that conviction included his dismissal of chilling documentation that Philadelphia prosecutors working for him had unlawfully withheld critical exculpatory evidence during Williams’ trial — a circumstance similar to documented evidence of prosecutorial misconduct in the Abu-Jamal case.

Attorney Judith Ritter, who along with Christina Swarns, litigation director of the NAAACP Legal Defense Fund, is arguing the case petitioning for a new PCRA hearing on Abu-Jamal’s conviction, called Judge Tucker’s discovery order “sweeping.” She said she expects the DA’s office to try to appeal that order right up to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, though she notes that such an appeal by the DA must first be approved by Judge Tucker. She said that while Castille’s role in overseeing the DA’s efforts to block Abu-Jamal’s appeal of his conviction differs from the exact details of the Williams v. Pennsylvania case, where Castille as DA actually oversaw the prosecution of the defendant at his initial trial, rather than the appeals process, as in Abu-Jamal’s case, “There are a number of petitions now being brought in Pennsylvania in response to the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Williams case, and some are similar to Abu-Jamal’s case.” Most, she said, are being filed by public defenders.

Swarns issued the following statement following Judge Tucker’s order:

“Today’s court order granting Mr. Abu Jamal’s motion for discovery reaffirms the importance of fairness and integrity in the criminal justice process. The decision was dictated by the United States Supreme Court’s decision last year in Williams v. Pennsylvania, where the Court held that the constitutional right to due process is violated when a judge presides over a case in which s/he had prior significant and personal involvement as a prosecutor. In Williams, Ronald Castille personally approved the decision to seek the death penalty as a prosecutor and subsequently presided over Mr. Williams’ appeals as a Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Mr. Castille similarly served as both a prosecutor and appellate judge in Mr. Abu-Jamal’s case – and 15 other cases—potentially compromising the fairness of the legal proceedings. Discovery is therefore appropriate in all cases in which Mr. Castille’s dual role may have violated due process.”

The unusual U.S. Supreme Court rebuke of Castille in the Williams case cited judicial conduct rules in Pennsylvania applicable to judges who had previously worked for a governmental agency like serving as a District Attorney. Those ethical conduct rules require judges to remove themselves from “a proceeding if [their] impartiality might reasonably be questioned” because of their former position with such a governmental agency.

That 5-3 U.S. Supreme Court ruling declared that an “unconstitutional potential for bias exists when the same person serves as both accuser and adjudicator in a case.”

That order made recently by Judge Tucker requires the Philadelphia DA’s office to produce all documents relevant to Castille’s role in the Abu-Jamal case when he served as the DA of Philadelphia, which covers a period of five years, from 1986-1991. An assistant prosecutor in the Philadelphia DA’s office since 1971, Castille became Deputy DA under then District Attorney Ed Rendell in 1983 and was elected to succeed Rendell in 1985. Castille was elected to the state’s Supreme Court in 1993, and was later elevated to the position of Chief Justice of that court in 2008. He retired from the court in 2014 when he reached the mandatory retirement age of 70.

Mumia supporters protest at the office of the Philadelphia District Attorney, which retired Justice Ron Castille headed for four years (Photo by Linn Washington)

Mumia supporters protest at the office of the Philadelphia District Attorney, which retired Justice Ron Castille headed for four years (Photo by Linn Washington)

Supporters of Abu-Jamal are calling Judge Tucker’s discovery order a rare victory in a lengthy string of appeals of Abu-Jamal’s conviction because courts have for decades rejected even the most appalling evidence of improprieties repeatedly presented in Abu-Jamal’s appeals despite those same courts often having already granted appellate relief to other inmates who had raised precisely the same issues as Abu-Jamal, often based on less evidence of official wrong-doing than found in Abu-Jamal’s case.

Lawyers for Abu-Jamal in 1997 had formally requested that Castille not participate in the deliberation over their client’s appeal and instead recuse himself because of his earlier role as DA and also because of his long association with Philadelphia’s police union, the Fraternal Order of Police. During his 26 years on Pennsylvania’s death row, the FOP was the leading advocate of Abu-Jamal’s execution, often organizing protests by police that featured banners calling on the courts to “Fry Mumia.” The FOP had given Castille Man-of-the-Year awards and provided political support and campaign cash for his election to DA and the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

That recusal request was based on Pennsylvania’s Code of Judicial Conduct provisions that urged judges to recuse themselves from cases where they “have personal knowledge of disputed evidentiary facts concerning” in that case and when their former employment by a “governmental agency” raises questions of impartiality.

Castille refused that request and instead participated in the court’s 1998 ruling against an Abu-Jamal appeal. He wrote a separate opinion along with the court’s ruling, presenting his reasons for rejecting a petition for his recusal — an opinion that included some bizarre explanations for his decision.

He stated for example that he had never “personally” participated in any aspect of the Abu-Jamal case as District Attorney. Using convoluted reasoning, Castille claimed that just because he had signed his name on DA Office filings opposing Abu-Jamal’s appeals as a “formal administrative requirement,” such actions did not prove that he had been “personally and directly involved” with those filings.

Yet, years before that decision, back when he was running for a seat on the state’s top court, a former top aide to Castille told a local reporter that his old boss, as District Attorney, “was involved in death penalty cases” and that he particularly had been involved in “high-profile cases.”

Since the Abu-Jamal case was both a death penalty case and a high-profile case, either Castille’s top aide misstated his ex-bosses’ role or Castille misrepresented it.

When Castille campaigned for his Supreme Court seat, he told voters in his campaign literature that he had been a “hands-on” DA. But when Abu-Jamal called for the former DA to recuse himself as a judge in ruling on his appeal, Castille claimed the exact opposite: that he had been a hands-off administrator as DA and that his role as DA would not affect his ability to be impartial as a justice.

Castille further claimed in his written rejection of Abu-Jamal’s recusal request that his participation in ruling granting relief to another Philadelphian convicted of killing a cop proved that he could be fair in Abu-Jamal’s case.

In that cop killing ruling that Castille authored, Castille stated that it was improper for a Philadelphia prosecutor to dramatize that defendant’s drug dealing in arguing for a death penalty against that drug dealer. But in the Abu-Jamal case, Castille contended it had been proper for Philadelphia Assistant DA Joe McGill to smear Abu-Jamal for his Black Panther Party membership as a young teenager when seeking the death penalty. The thing is, Abu-Jamal’s BPP a membership had ended 12 years before his arrest in the shooting death of Officer Faulkner, while the drug dealer cited by Castile had been involved in a series of violent drug-related incidents, including on the day he killed the policeman. (Abu-Jamal did not have an arrest record like the drug dealer cited by Castille.)

Castille took his bizarre reasoning further into the realm of the absurd when he brushed off his long association with Philadelphia’s FOP police union. Not only did he deny any improper influence from his FOP associations and the financial support he had received in his various political campaigns from the union; he also declared that Abu-Jamal was unfairly criticizing him without criticizing the four other Supreme Court justices on the bench who had also received campaign support from the FOP. Those four court colleagues of Castille also voted against Abu-Jamal’s appeal.

Castille, in defending himself against any FOP taint, exposed the indefensible underpinning of that 1998 ruling: the fact that five members of that seven-member Court had received FOP support –- a prime example of the grounds listed in the judicial ethics code for their impartiality being reasonably questioned.

Castille wrote: “If the FOP’s endorsement constituted a basis for recusal, practically the entire court would be required to decline participation in this appeal.”

In Castille’s twisted logic, it was more important for FOP-tainted justices to rule on an appeal in which the FOP was profoundly interested, than that that those justices act to uphold the constitutional right of an appellant for a fair and just judicial ruling.

Castille’s participation in the state Supreme Court’s rejection of Abu-Jamal’s appeal is one reason why the February 2000 Amnesty International report on Abu-Jamal criticized the “appearance of judicial bias during appellate review.”

So far, most Philadelphians don’t even know about Judge Tucker’s discovery order to the DA’s Office, as neither the Philadelphia Inquirer nor the Daily News has deigned to report about it, even as a short news item, though both papers did major reports on the Williams case last year and its significance for other similar cases where Castille did not recuse himself despite prior involvement in those cases as DA. So much for quality journalism in the city where the press was enshrined in the Constitution as a “fourth estate” of people’s government.

The authors of this article have both covered the Abu-Jamal case for decades, Linn Washington as a columnist for the Philadelphia Tribune and Dave Lindorff as a freelance journalist and as author of a book on the case, “Killing Time: An Investigation into the Death Penalty Case of Mumia Abu-Jamal (Common Courage, 2003).